A science fair project by Maddy Scannell, 4th grade.

If you haven't done the experiment yourself, please give it a try before reading the results below! You can get to the experiment by clicking here.

What effect does a person's native language (IV) have on his/her ability to distinguish colors (DV)?

I predict that a person's language will have an effect on their ability to distinguish colors. For example, if someone speaks a language with not very many words for different shades of red, let's say, then I predict that it would be difficult for that person to distinguish shades of red.

Linguistic relativity is the idea that people who speak different languages think different ways. This idea came from Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf.

Edward Sapir was an anthropologist and linguist. He was also a colleague/teacher to Benjamin Whorf. Sapir lived from January 26, 1884, born in Lauenberg, Prussia, until February 4, 1939, in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. He was also the author of Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. He was a star student of Franz Boas.

Franz Boas was often credited as the founder of anthropology in the United States. Boas was educated in Germany in the late nineteenth century. He lived from July 9, 1858, in Minden, Westphalia, Germany, to December 21, 1942, New York. He married Marie Krackowizer who lived from 1861 to 1924. They had six children. As Boas studied different cultures, he realized how much ways of life and grammatical categories may vary from place to place. As a result, he came to hold that the culture and lifeways of people are reflected in their language.

Benjamin Whorf lived from April 24, 1897, born in Winthrop, Massachusetts, United States, until July 26, 1941. He graduated from MIT in 1918 with a degree in chemical engineering. Shortly afterwards he began work as a fire prevention engineer. Although he met and studied with Sapir, he never took up linguistics as a profession. Whorf's primary interest in linguistics was the study of Native American languages. He became well-known for his work on the Hopi language. He was considered to be a captivating speaker and did much to popularize his new linguistic ideas and thoughts through well-known articles and lectures.

Apart from being famous for his work on the Hopi language, he is also well-known for the so-called "Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax". This happened when Whorf announced in one of his articles that the Eskimo (or their correct names the Inuit and Yupik) had many words for snow. In 1940, he wrote:

We have the same word for falling snow, slushy snow, snow on the ground, snow packed hard like ice, wind-driven flying snow, whatever the situation may be. To an Eskimo, this would be almost unthinkable; he would way that falling snow, slushy snow, and so on, are all sensuously and operationally different, different things to contend with, he uses different words for them and for other kinds of snow.

But the Eskimo do not have 400 words for snow. Whorf did not know about this at all. This idea was proved false by anthropologist Laura Martin. She wrote a paper proving this.

Even with all of the experiments done on linguistic relativity, no one is completely sure if it is true or not, because of all of the reasons for and against it. The arguments against it are something like this. First of all, the people who are against it find flaws in the arguments that Whorf made in favor of it. For example, they showed that Whorf was wrong about the Eskimo's words for snow. They also pointed out that Whorf never met any Hopi Indians so he had no way of knowing what he thought, except by looking at their language, which makes his argument circular. Their real argument is that human brains and eyes are all the same and that the language you grow up speaking shouldn't affect your ability to perceive colors or any other things.

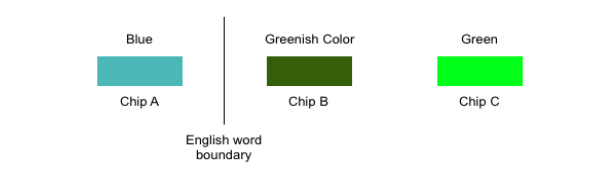

The arguments for those in favor of linguistic relativity are pretty much all experiments. One of them was conducted by Kay and Kempton in 1984 with English speakers and Tarahumara speakers (a language in Mexico). They showed them three color chips. One was what we would call a "blue", one was what we could call a greenish color and one was clearly green:

A is blue, C is green, and B is closer to A in terms of the actual color, but since English speakers have a word boundary between green and blue, or A and B, they almost always said chip B was closer in terms of color to chip C. Tarahumara speakers have one word for blue and green and said (correctly) that B was closer to A.

Because there are arguments both for and against linguistic relativity, no one is quite sure if it is true or not. That is why I decided to do my own experiment on linguistic relativity.

First you have to set up the experiment on a web site so that anyone with an Internet connection can access it. The experiment involves three web pages: a welcome page with instructions, a form for entering color names and a form for selecting colors from a palette. The responses are stored on a web server. My Dad helped me set this up.

Second you have to contact friends and family asking them to do the experiment. Then direct them to the web site.

Finally collect the file of all responses from the web site so they can be analyzed. For example, let's say we wanted to measure the average that people made for color number three. The first thing you would do would be to list all the nearby guesses. Next you would subtract three from that numbers and turn negatives into positives. This tells you how far off their guess was. Next square those answers (multiply the numbers by themselves), average them and take the square root of that.

Next we need a way of getting a number from how much variety there was in peoples' choice of color names. What you would do is take a color, say, blue, and see what different color names people called it. You would divide the different names into fractions, such as below. Let's say there were eight people who got this blue, but only five-eighths of them called it "blue". Only two-eighths called it "turquoise", and only one called it "aqua". You then use a calculator or spreadsheet to compute the entropy. Entropy is the randomness of something or how much variation there is. So if everyone uses the same name for a color, the entropy is zero and the biggest it can be is when everyone uses a different name. The formula in the case above is -5/8 log(5/8) - 2/8 log(2/8) - 1/8 log(1/8).

In all, more than two hundred people took the experiment and 3219 colors were shown. People did the experiment in 34 languages. There was only enough data to analyze nine languages: Afrikaans (85 colors), Basque (111 colors), Chinese (98 colors), Dutch (135 colors), English (1116 colors), French (118 colors), Irish (350 colors), Spanish (316 colors), and Turkish (114 colors).

Here are the scatter graphs showing the relationship between color-name variety and average error in people's guesses, for the nine languages above:

Here is the same information, but plotted on graphs with colors on the x-axis.

My hypothesis was that there was such a thing as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. This means for my experiment that people who speak languages with more color words should have an easier time guessing those colors. This would mean there should be a downward slope in my graphs above with "error" on the x-axis and "color variety" on the y-axis. The three languages with the most data (English, Irish, and Spanish) had nearly flat or slightly upward slopes. So my hypothesis was wrong for these languages. Also, for all of the languages, the points weren't very close to the line at all. The rest of the languages had mixed results, some going down showing signs of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (Dutch, Basque), and others sloped up or were flat. I wonder if the other six languages had more data they would be flat or slant upwards too.

My experiment was not as perfect as it could have been. One thing was that to do a really good experiment you would need a huge group of people so I would get more experimental subjects.

Doing the experiment on a computer is an easy way of getting lots of data but there is no control over who does it. Also people could repeat the experiment and this is not good because then there is a practice effect which means people get better at it when they do it more times. Plus people can quit the experiment during the middle of it. The people who did the experiment were also not randomly chosen, they were selected by me. Also you can't control people who might be colorblind or have bad vision.

To test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis even better, we should consider other ways people think, because the hypothesis is broader than just the way people perceive colors.