CSCI-1080 Intro To CS: World Wide Web

Saint Louis University, Department of Computer Science

Games: Competition and Cooperation

Dynamics of popularity and influence

PageRank measures influence at one moment in time. What happens when Web builders seek to improve their rankings? What principles explain the resulting competitive dynamics? We begin our analysis with the following assumptions:

All Web surfers (and builders) use Google and similar search engines to find Web pages.

All Web builders know that their popularity is largely determined by Google search results.

To the above scenario, we now add the assumption that all Web builders understand PageRank. Perhaps some Web builders have even read our preceding chapter. This Web-builder knowledge transforms the above scenario in a significant way:

Each Web builder knows that increasing the PageRank of his work requires other Web builders to link to it. Improving his own rank means his peers must be convinced to help him.

Each Web builder knows that the PageRank of his work is meaningful only as a point of comparison to his peers’ work. Improving his own rank means the same thing as diminishing the rankings of his peers. In other words, Web builders’ desire for popularity, combined with knowledge of how to win popularity, leads inevitably to a mix of both competition and cooperation. We finally add one last assumption:

Each Web builder not only understands the competition and cooperation inherent to this system, but also expects that every other Web builder has the same understanding. Therefore, when two Web builders interact, each one recognizes a mutual desire to exploit the other and a shared investment in building the Web.

PageRank competition

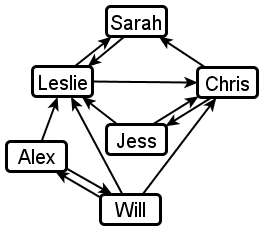

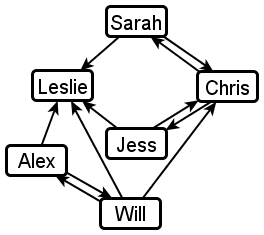

Consider the six-page mini-Web drawn below. Each page is named after its author. PageRank computes the following rankings (using a damping factor of 0.85) for this mini-Web:

|

Rankings:

Leslie (1.929)

Sarah (1.542)

Chris (1.345)

Jess (0.722)

Will (0.243)

Alex (0.219)

We assume that each of these Web builders wants to improve her/his rank and will do what s/he can to change the network to that end. We also assume no new Web builders join the network. Below are steps that each person in the top-ranked trio (Leslie, Sarah, Chris) might consider in order to win the top ranking:

Leslie is in first place. She can do nothing (for now).

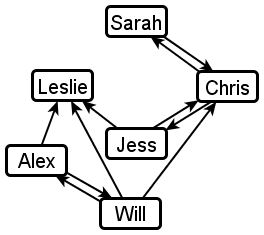

Sarah can take first place by deleting her link to Leslie. Sadly for Sarah, Leslie can retaliate and still win by deleting her links to Sarah and Chris. Sarah ends up dropping to third place.

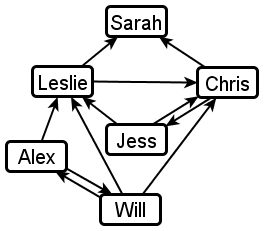

Sarah deletes her link to Leslie:

|

Sarah (0.608)

Chris (0.596)

Leslie (0.483)

Jess (0.403)

Will (0.243)

Alex (0.219)

Leslie retaliates:

|

Leslie (0.438)

Chris (0.345)

Sarah (0.297)

Jess (0.297)

Will (0.243)

Alex (0.219)

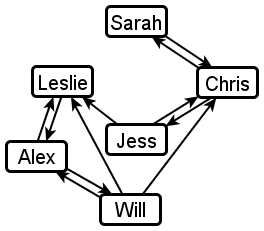

Chris can take first place with Sarah's help (i.e., if Sarah links to Chris). Sarah may be happy to help Chris, because Chris is already linking to Sarah, and Sarah does not lose anything by helping Chris.

Below we see the initial alliance of Sarah and Chris, followed by retaliation from Leslie. Leslie's return to first place lasts only until Sarah strikes back and deletes her link to Leslie. Thanks to Sarah's unswerving loyalty to Chris, the Chris & Sarah alliance ultimately keeps Chris in first place.

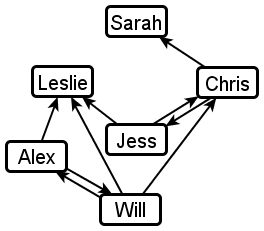

Sarah agrees to help Chris:

|

Chris (1.805)

Sarah (1.483)

Leslie (1.332)

Jess (0.917)

Will (0.243)

Alex (0.219)

Leslie deletes her links to Sarah and Chris:

|

Leslie (0.635)

Chris (0.542)

Sarah (0.380)

Jess (0.380)

Will (0.243)

Alex (0.219)

Sarah deletes her link to Leslie:

|

Chris (0.895)

Leslie (0.537)

Sarah (0.530)

Jess (0.530)

Will (0.243)

Alex (0.219

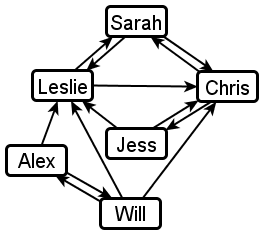

Surprise ending: Leslie recognizes that she needs her own alliance to defeat the combined forces of Chris & Sarah. Leslie teams up with Alex, because Alex has already linked to Leslie but not to Chris. Leslie catapults Alex from last place to first, with one link (below). Alex may be trusted to share the spoils of his victory with Leslie, because Leslie can put Alex back into last place anytime she wants.

Leslie & Alex defeat Chris & Sarah:

|

Alex (1.435)

Leslie (1.258)

Chris (1.215)

Will (0.760)

Sarah (0.666)

Jess (0.666)

Doing the right thing

The important features of PageRank competition are the broad generalities, not the details of any particular contest. In particular, we observe that typically

It is good for your rank when others link to you.

It is bad for your rank when you link to someone else who is not already linking to you.

It can be good for your rank when you link to someone else who is already linking to you.

These factors affect the behavior of any Web builder who cares about the visibility of her work. Each time a Web builder considers linking to someone else's site, she faces some immediate tradeoffs:

Benefits of linking

Web builder provides her audience with easy access to related sites.

Web builder improves search rankings of other sites she likes and links to.

Web builder contributes to the construction of a meaningful Web.

Drawbacks of linking

Web builder makes it easier for her audience to leave.

Web builder may diminish search rankings of her own site.

Web builder makes it easier for the work of others to supersede her own.

When a Web builder links to someone else's site, the immediate benefits spread widely, but the immediate drawbacks fall squarely on her. We therefore consider linking as an example of doing the right thing–acting in a way that is helpful to the common good but costly to self.

Other examples of doing the right thing include:

Doing the laundry when it is your turn, so that your partner can do likewise

Donating to charity, rather than spending the money on yourself

Waiting in line, rather than wangling your way to the front

Doing the right thing in each of these situations means cooperating instead of competing, and accepting the risk that someone else may exploit your generosity.

Mutually assured construction

The above analysis of benefits and drawbacks focuses purely on short-term outcomes of linking or doing the right thing. What about long-term outcomes? After all, the point of analyzing dynamics is to understand changes over time – both now and later.

Six Degrees chapter 7 introduces the notion of coordination externalities to integrate the short-term and long-term perspectives of doing the right thing. The influence of coordination externalities boils down to this: I will sacrifice my short-term selfish interests for long-term gains that depend on favors from others, to the extent that (1) I care about the future, and (2) I believe my actions affect the decisions of others.

Example: When my friend lends me 10 dollars, I will pay him back the next time I see him. I lose 10 dollars when I pay him back but gain more than that in the long run. Maintaining our friendship is worth more to me than 10 dollars.

Coordination externalities influence Web builders to the extent that the following are true:

Each Web builder can potentially benefit from favors from others. Any Web builder who cares about the popularity of her work clearly fits this description. Her ranking and popularity will improve if other Web builders link to her.

Each Web builder cares about the future. In particular, this includes caring about the future of her work. For most Web builders, this seems like a reasonable assumption. Casual Web-building hobbyists and malicious hackers may not care about the future of their work. The rest of us care about the future of the Web and our place in that future.

Each Web builder believes that her actions affect the decisions of others. In particular, this includes believing that her Web programming influences others. Again, for most Web builders, this seems like a reasonable assumption. This is true partly because Web links are public: the act of linking and the act of reciprocating a link (or not) are visible to all who care to look. Anyone affected by someone else's linking can respond accordingly.

Thanks to the influence of coordination externalities, we therefore expect that a typical Web builder will do the right thing and link to other sites in good faith – even if some of those links risk diminishing the short-term popularity and influence of her own work. Web building is a game of mutually assured construction.

Authority, reciprocity, and reputation

Sometimes a group takes extraordinary steps to make sure that each individual does the right thing. The framers of the United States Constitution are a good example. They explained their motives famously:

“We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The rest of the Constitution, among other things, invests authority in the United States Government to write laws (defining what it means to do the right thing) and to enforce laws (punishing individuals who do not do the right thing). For example, someone who gets caught robbing banks goes to jail; that gives anyone under the authority of the United States Government an incentive to do the right thing and not be a bank robber.

We are interested in coordination externalities specifically in situations where there is no operating authority. Recall our examples of doing the right thing: doing laundry, donating to charity, waiting in line, and linking to someone else's site. In all these situations, no authority imposes a penalty on individuals who do the wrong thing. You will not get arrested for laziness after your partner picks up your dirty socks for you.

In the absence of formal laws or government, the influence of coordination externalities represents a different kind of authority that is informal and collective. Reciprocity and reputation are two distinct ways that this informal collective authority influences individuals to do the right thing:

Reciprocity applies to situations where two specific individuals expect to interact repeatedly. For example, after I borrow $10 from my friend, we both expect to see each other again, and we both want those interactions to be fun and fruitful. That motivates us to cooperate with each other.

Reputation applies to situations where each individual has, literally, a “good name” to protect. Even if two specific individuals will never see each other again, each individual knows the current reputation of the other and can affect the future reputation of the other. For example, suppose I try my friend's hair stylist for a cut, and it's my last week in town before I move to start a new job. Even if the stylist knows that I will never see her again, she still knows that I can affect her reputation (e.g., by telling my friends what I think of her). This gives the stylist an incentive to do a good job.

Food for thought: Why is the notion of reputation especially important for a site like eBay? Think about this from the perspective of eBay's users (buyers and sellers), eBay's owners, and the programmers who build eBay.

Game theory

Game theory is a branch of mathematics that models situations with multiple players, each of whom chooses in some way to compete or cooperate. Some problems of game theory are especially famous:

Prisoners’ dilemma: Arguably the most famous problem in all of game theory. A fun and easy version of the game can be played here; see also “what's so important about this game.”

Diners’ dilemma: You and your friends are eating out and plan to divide the tab evenly. Do you splurge at your friends’ expense or eat light and pay for someone else's steak? See Six Degrees p. 202.

The following two scenarios also relate to game theory. They are called “tragedies” because each scenario assumes that the players choose to compete rather than cooperate:

Tragedy of the commons: If an asset (a grazing field, say) is held in common, each individual will try to exploit as much of it as possible. Because of overuse and lack of ownership, the common asset will soon be destroyed. See Six Degrees pp. 203-204.

Tragedy of the anti-commons: If too many people own individual parts of an asset, it’s easy to end up with gridlock, since any one person can simply veto the use of the asset. Linux, the most popular Web-hosting operating system in the world, is such an asset that was almost vetoed out of use by a single person.

See “The Permission Problem” by James Surowiecki in The New Yorker for the concept.

See “Toppling Linux” by Daniel Lyons in Forbes for the case study.

The winners’ dilemma

An important result of game theory is that, for many games, there is no single “best” strategy. How an individual maximizes his score in a game depends on the strategies chosen by all the other players.

In the presence of coordination externalities, the following principles guide a strategy that can succeed against a wide variety of other players:

Be nice: Start by cooperating and never be the first individual to exploit another player.

Be provocable: After another player exploits you, quickly retaliate.

Be forgiving: After another player stops exploiting you, quickly resume cooperating.

Most of us are happy to embrace these principles. So, if being nice, provocable, and forgiving is all it takes to win prisoner's dilemma and diners’ dilemma, then what is the “dilemma”?

The dilemma in these games arises when coordination externalities are absent. By definition, coordination externalities are absent if at least one of the following is true:

A player does not seek any long-term gains that depend on favors from others.

A player does not care about the future.

A player does not believe his actions affect the decisions of others.

If at least one of the above factors is true (i.e., coordination externalities are absent), then the principles of a winning strategy for that player are starkly simple:

Compete: Pre-emptively exploit every other player as much as possible.

Sadly, when all the players choose this “winning” strategy, the unmitigated competition causes a “tragedy” in which everyone loses. If only everyone were to choose the “losing” strategy and cooperate, they'd all be better off – until someone got smart, competed, and exploited all the cooperating losers. Why cooperate, when you're sure to get exploited? Better to choose the “winning” strategy in which everyone loses. Hence the dilemma.

The contect of this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.